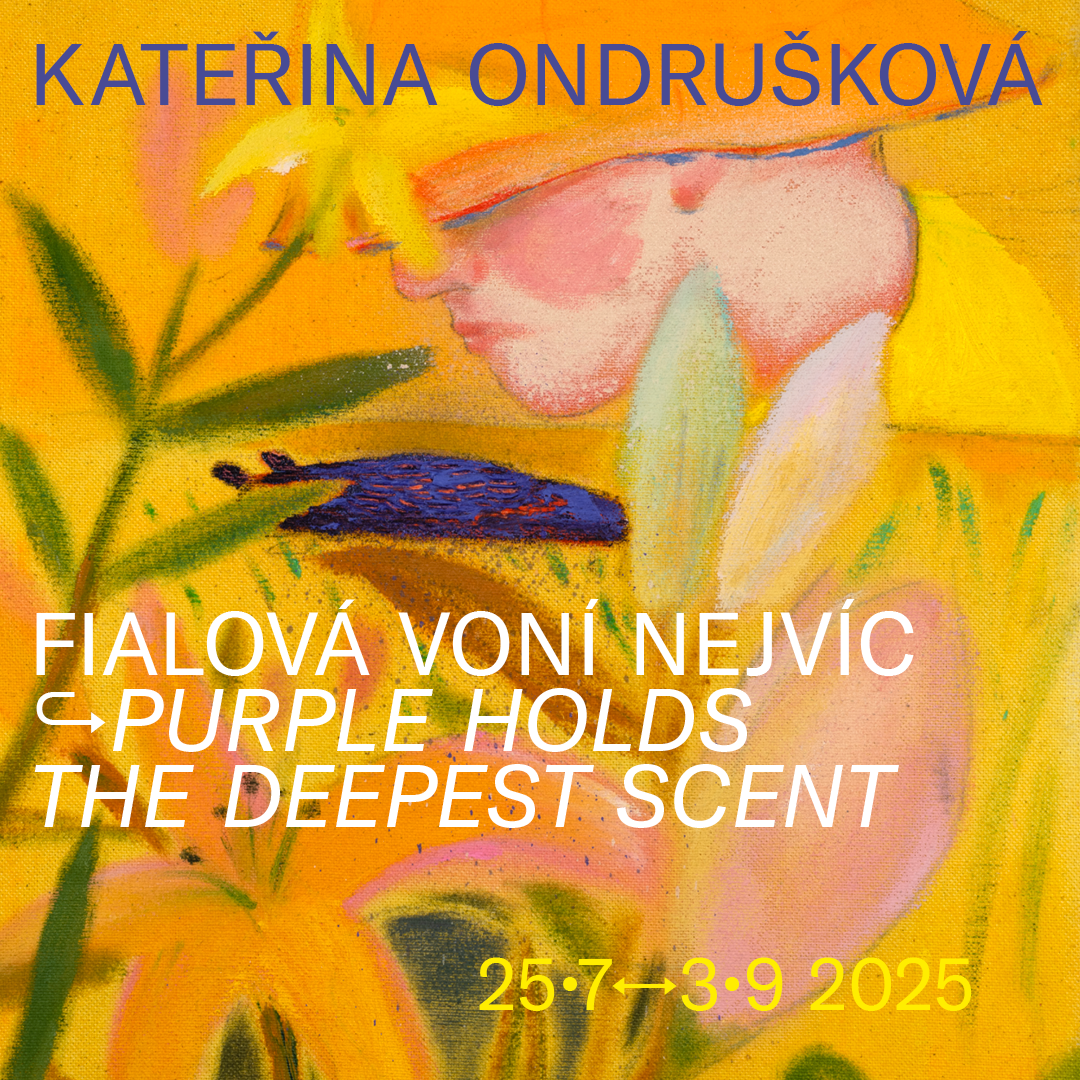

Kateřina Ondrušková

Though it may not be apparent at first glance, the painterly world of young artist Kateřina Ondrušková is intrinsically linked to everyday life. The flood of colours, symbols and signs acts as a kind of mimicry, subtly concealing something. They are layers in which the creative process of the poeticisation of reality takes place. The attributes of the everyday undergo transformation. The artist removes them from the realm of reflective, naturalistic description and elevates them to the timeless sphere of symbolic communication. We find ourselves in the midst of a meta-narrative that generalises three main themes, using the expressive means of painting to address parenthood, motherhood and the interpersonal relationships associated therewith.

Ondrušková brings to contemporary young Czech painting a sensitivity to objects, phenomena and events, which she renews through her unique visual style in their timeless, cyclical validity. How does a child see? How does a mother? What exactly changes in a person? What role does each person play? Ordinary reality seems to split into the polarities of ritual and dream alongside quotidian concerns. Just as a mother splits herself in two and gives part of herself to the creation of a newly born being, so in the next phase of motherhood she “sees with different eyes” the world around her. A “garden” of the shared imaginary emerges, in which reminders and references to her own childhood, to the landscape in which she grew up, to the artist’s memories and recollections multiply, along with links to signs that explain the presence of children in a hitherto unknown and hence magical space based more on dreams and the pleasure principle than on the numbing reality principle.

Ondrušková opens windows onto paradises that can be recalled in a Proustian manner and involuntarily brought to mind. She evokes paradises where “violet has the strongest scent” and every flower and every animal represents the promise of an open and sun-drenched future, a certainty that everything will inevitably repeat itself because “it is good”. The image functions here as a repetitive narrative in which particular characters are gradually transformed into general symbols, and concrete experiences into a movement of initiation. We are introduced into a time whose fall (haste) has slowed down. A timelessness with fairytale features emerges.